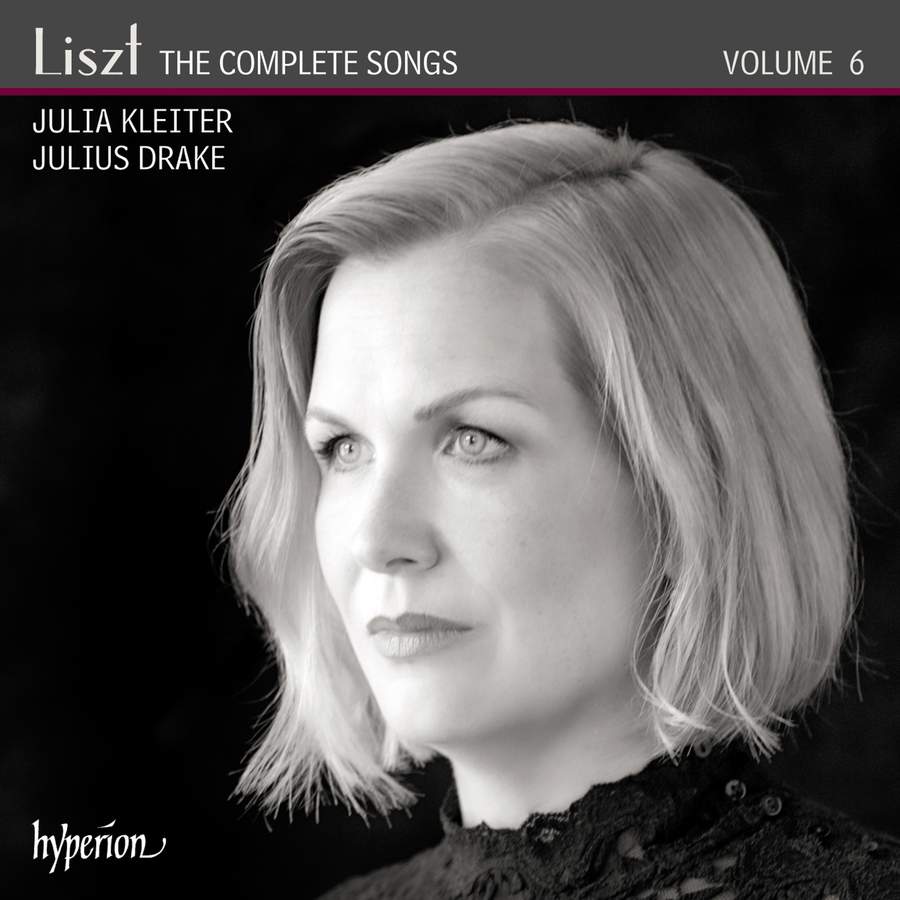

Liszt: The Complete Songs, Vol. 6 - Julia Kleiter

Liszt: The Complete Songs, Vol. 6 – Julia Kleiter

2020 | Hyperion

Julia Kleiter (soprano)

About

With this instalment of the series, we once again encounter Liszt the cosmopolite, Liszt the friend of the Hochadel (high aristocracy), and Liszt the perpetual tinkerer with his own works. Once again we go back and forth between initial versions of a song, when the composer’s response to the words was new, and later versions, when an older, sadder, but always restlessly experimental composer was exploring avenues different from those of the firebrand in the 1840s.

When the poet Franz von Dingelstedt was fired as intendant of the Munich court theatre on trumped-up charges in 1856, the generous Liszt helped him to obtain a similar post in Weimar, but two years later, Dingelstedt would be the prime mover and shaker in Liszt’s forced resignation as Kapellmeister. The wordsmith was known primarily for his political verse, but in 1845 Liszt chose a more conventional love poem (clichés abound) by this poetic mediocrity, Schwebe, schwebe, blaues Auge, in which the sweetheart’s blue eyes make springtime blossom and warble in the persona’s heart. We hear Liszt’s first version, with its downward drifting sighs of longing in the piano introduction, swaying motion in the singer’s part, a joyous excess of birdsong trilling midway, a plethora of high notes, and a wonderfully curvaceous vocal descent to the final cadence. Liszt’s signature harmonic and tonal audacity is amply in evidence: the progression in which we go from F minor on ‘night and winter’ (‘Nacht und Winter’) to day’s sudden arrival on D flat, and then to a blaze of A major for ‘Day and May’ (‘Tag und Mai’), is par for the course.

Liszt was close friends with Prince Felix von Lichnowsky, the grandson of Prince Karl Alois, whose relationships with Mozart (Alois sued him) and Beethoven (who smashed a bust of the prince) make vivid reading. Felix would be murdered in a gardener’s hut by revolutionaries in 1848, but seven years earlier he and Liszt were travelling together and came upon the island of Nonnenwerth in the Rhine, where Roland of Roncevaux supposedly died of love (a legend) and where Liszt and Marie d’Agoult lived for a time. Liszt set Lichnowsky’s poem Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth for voice and piano in German (1843); there followed various arrangements for solo piano, song versions with French text (1844 and 1845), an 1858 (published 1860) version for baritone and piano with German text, and an arrangement for violin or cello with piano in 1883(?). Here we hear Nonnenwerth for soprano and piano in its first version, which begins with bell-like chiming minor chords (A minor to F minor) that drift downwards and culminate in a single sustained pitch in the bass. After this exquisitely evocative introduction a barcarolle in the conventional 6/8 metre for water music leads to the song’s first climax at the invocation of the legendary Roland. The opening music now in major mode gives way to enharmonic motion to the ‘dark side’ of the tonal realm and then to a passionate plea that the beloved return. The song ends with a gentle echo of the opening harmonies, the mixture of major and minor chords (A major and F minor) a beautifully encapsulated rendering of love and loss.

Liszt first set the Austrian journalist and travel writer Johannes Nordmann’s Kling leise, mein Lied on 30 March 1848 and then revised it for publication around 1859. We hear the later version, whose introduction is shortened, with the earlier syncopated melody in the right hand no longer in evidence, and hand-crossing bells chiming in the treble instead. Liszt additionally omitted passages containing the second and third stanzas and directs that the injunction to ‘Entwine her tenderly, as the tendril entwines / In love the tree’ (‘Umschlinge sie sanft, wie die Ranke den Baum / In Liebe umschlingt’) be ‘almost spoken’ (‘fast gesprochen’). In both versions harp-like arpeggios accompany the return of the initial stanza. In 1857 Liszt wrote to the lyric tenor Franz Götze (1814–1888), saying thus: ‘I very much wish that you would do me the kindness of singing two of my songs [in Leipzig]: “Kling leise, mein Lied”, and “Englein du mit blondem Haar”, and delight the public with your ardent and beautifully artistic rendering of these little things.’

The great French Romantic writer Victor Hugo once put an advertisement in Le Figaro begging composers not ‘to set tones alongside my words’, but this did not stop them from gravitating to his beautiful poetry. We hear the second/later versions of four of Liszt’s greatest songs, and once again he revises for greater concision and more delicate textures. For example the second stanza of Oh! quand je dors was completely rewritten, its enharmonic modulation typical of its composer—but the magical ending that ascends straight up into the heavens where Petrarch adores his Laura is still there. The previously hyperbolic accompaniment to the c1844 version of Enfant, si j’étais roi is trimmed down considerably in the later version. Here the rhythmically off-centre semitone figures in the left hand and the thrumming repeated chords in the right beautifully bespeak passion’s restless energy; after a rampaging episode of cosmic thunder, Liszt returns to Love, in a final cadence made irresistible by hints of the parallel minor. In both versions of S’il est un charmant gazon Liszt omits Hugo’s second stanza, with its wish for a loving and noble breast to become the pillow for the beloved. A near-constant murmuring of Nature’s gentle voices in the piano gives way to breaks in the instrumental sound for the wish at the end of each stanza. Comment, disaient-ils is a question-and-response song ostensibly between men and women, with the men asking how to escape the pursuing law (the alguazils, or the Spanish/Portuguese police), how to forget misery, and how to win love without enchantments. ‘Row’, ‘Sleep’ and ‘Love’ (‘Ramez’, ‘Dormez’ and ‘Aimez’) are the pithy answers, set to octave leaps upward. ‘Like a guitar’ (‘quasi chitarra’), Liszt tells the pianist who accompanies this serenade.

The character Mignon in Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre was kidnapped from her native Italy by a troupe of travelling acrobats and subsequently rescued by the title character Wilhelm, with whom she falls in love. A mysterious and profound creation, she symbolizes humanity’s two natures, earthly and spiritual, male and female, and her gestures, mannerisms and language mimic the symptomatology of an abused child; she is furthermore the spirit of Romantic poetry within Goethe. In songs such as Mignons Lied (‘Kennst du das Land?’) she reaches for the lost and irretrievable ideal. Goethe tells us that she sings with ‘a certain solemn grandeur, as if … she were imparting something of importance’, and Liszt imbues his first version of a poem that fascinated many a composer with all the passionate intensity of late Romantic music. The first section of each stanza, painting pictures of her bygone home and country, features a wistful falling figure in the piano, followed by repeated questions that reach upwards in hope, and a refrain impelled to greater movement as she dreams of going back home.

Musicians know Ludwig Rellstab as the poet of the first seven songs in Franz Schubert’s Schwanengesang, D957, and the man who invented the nickname ‘Moonlight Sonata’ for Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C sharp minor, Op 27 No 2. In his own day he was an influential music critic, travel writer, novelist (whose 1812 fictionalizes Napoleon’s Russian campaign before Tolstoy got around to it), and poet. In Wo weilt er? Rellstab uses the litany format we find in ‘In der Ferne’ from Schwanengesang: here an unknown voice asks a series of brooding questions (‘Where does he dwell?’, ‘Where does he rest?’, ‘What does he think?’), receiving pessimistic answers each time (‘In the cold and gruesome land’, etc.). In the final section the singer passionately implores someone beloved to come home.

Liszt set Wo weilt er? twice—his frequent recourse to re-composition and multiple versions is evident yet again. The first version was only published in the Liszt Society Journal in 2012; it is quite wonderful to realize that new discoveries are still possible in music scholarship. We hear the second version, a masterful example of Liszt’s mature musical language in the 1850s; neither a stock ‘Lied’ and not opera-aria-like (but very dramatic), this is as far from salon songs as one can get. The initial chromatic chords rise in three stages: three non-verbal questions with no answer as yet, before the singer—now unharmonized for maximum starkness—repeats the last of the three questions posed in the piano introduction. These queries are the musical material from which the entire song is drawn.

Die Loreley, a descendant of Homer’s sirens (a golden-haired archetype of erotic female power created by the Romantic writer Clemens Brentano), sits atop a rocky promontory on the River Rhine and lures sailors to shipwreck with her beautiful singing. Heinrich Heine’s poetic masterpiece about the fatal power of the myth so entranced Liszt that he returned to his first thoughts many times over the years, publishing three further versions for voice and piano, the last of which was also given an orchestral accompaniment. At the beginning we hear music premonitory of Wagner’s Tristan, while the Loreley is described in melodic lines that yearn upwards, as if gazing at the cliff-top, followed by pianistic waters frothing and foaming as catastrophe ensues. The music emblematic of the Loreley’s singing is in the wordless piano: Liszt the great pianist seduces his listeners with the siren’s song.

Most scholars now consider Wilhelm Tell, who supposedly rebelled against Austrian domination in the fourteenth century and helped found the Swiss Confederation, to be fiction, but 200 years ago many people believed the sixteenth-century Swiss historian Aegidius Tschudi’s inventions. Goethe considered writing a play on the subject and then gave the idea to his friend Friedrich von Schiller, who wrote his drama Wilhelm Tell in 1803/4. (Adolf Hitler, initially enthusiastic about the play in Mein Kampf, banned it in 1941. ‘Why did Schiller have to immortalize that Swiss sniper?’, he reportedly said.)

Act I begins with three Rollenlieder (character songs) for a young fisherman, a herder and an alpine huntsman. Schiller directed that each song be sung to a ranz des vaches, the horn melodies played by Swiss herdsmen as they drove their cattle to and from pasture (a type of folk music much romanticized in the nineteenth century). The first song, Der Fischerknabe, is Schiller’s nod to the Germanic water mythology of nixies, sirens and mermaids, and Liszt in the 1840s created pianistic water music of dazzling virtuosity, along with a stratospheric part for the death-dealing nixie. But some ten years later he believed that songs should be simpler and therefore deleted the thunderous calls from the deep in the piano, the long wordless melisma for the singer at the end, and the high B sustained for five bars. Instead of triumph we hear dying-away sweetness at the end of this later version.

With Der Hirt, Liszt sets a text that Robert Schumann would claim four years later as ‘Des Sennen Abschied’, Op 79 No 22 (from the Lieder-Album für die Jugend of 1849): a wistful shepherd leaves the meadows at summer’s end, promising to return when it is spring again. In Liszt’s virtuosic first version we hear a plethora of pastoral effects: an evocation of the ranz des vaches, long-drawn-out horn calls, the cuckoo calling, the brook flowing mellifluously, and distant thunder in the piano postlude as a corridor to the third song. In the later version all of those pictorial elements are still there but moderated and abbreviated. The enharmonic swerve (Liszt is a master of such shifts) to bespeak earth clad anew with blossoms is magical. The first version of Der Alpenjäger was a thrilling battering ram, and Liszt shortened it drastically when he revisited the song. The original song delighted in repeated thundering heights and in a reminiscence of the fatal nixie from the first song, but she is nowhere to be seen or heard the second time around.

Helene zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1814-1858) was a French Crown Princess after her marriage in 1837 to Ferdinand Philippe of Orléans. In addition to introducing the German Christmas tree tradition to France, she wrote the text for Liszt’s Die Macht der Musik, presented here in its c1848 version (published in 1849). For this encomium to music’s powers Liszt begins with a long, atmospheric piano introduction that reminds us of his fascination with augmented triads used in unconventional ways. He further gives us operatic recitative style to dramatize ‘Having lost what makes life dear’, followed by a lyrical welcome to music’s sounds in Liszt’s sweetest doubled thirds in the right hand, arpeggiated harp figures in the bass, and expansive lyrical melody for the singer. Wafting treble breezes to hail the zephyr lead to a passionate invocation of memory, a majestic ode to ‘mighty music’ (with pomp and circumstance in the piano), and brief sorrow over the lies told in supposed friendship and love. But waves of rejoicing properly close out this massive song in a celebration of music’s ability to make the heart rejoice.

The very existence of Quand tu chantes, bercée was little known until published as part of an article by István Kecskeméti in Magyar Zene (‘Hungarian music’) and The Musical Times in 1974. Liszt set only the first stanza of a four-stanza serenade sung by Fabiano Fabiani, the fictional favourite of Mary Tudor (the sixteenth-century ‘Bloody Mary’, daughter of Henry VIII), to Mary’s (married) lady-in-waiting Jane; the historical Lady Jane Grey and her father-in-law John Dudley lurk in the background of Hugo’s drama Marie Tudor. Liszt never published this salon-song version of a berceuse, a sweetly erotic evocation of cradling motion, with an ascent into Love’s empyrean heights near the end.

Susan Youens © 2020