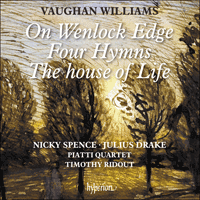

Vaughan Williams: On Wenlock Edge & other songs

Vaughan Williams:

On Wenlock Edge & other songs

2022 | Hyperion

Nicky Spence (tenor) & Julius Drake (piano)

About

I must … thank you for introducing me to the man who is exactly what I am looking for. As far as I know my own faults he hit on them all exactly & is telling me to do exactly what I half feel in my own mind I ought to do—but it just wanted saying.

These words occur in a short letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams (hereinafter RVW) to the French-born Greek musical author and critic Michael (Michel-Dimitri) Calvocoressi, written in a Parisian hotel. The appearance of ‘exactly’ three times within two sentences may reflect more than mere excitement, since the object of RVW’s enthusiasm was nothing if not precise. The French composer Maurice Ravel was at this time well established in his homeland but little known in England. Moreover, he was three years RVW’s junior. Those facts point to both the improbability of Calvocoressi’s perceptive tutorial recommendation and the humility of RVW in taking it up. The first encounter with Ravel could have gone awry: in his essay ‘A Musical Autobiography’ (1950), RVW recollected that:

He was much puzzled at our first interview. When I had shown him some of my work he said that, for my first lesson, I had better ‘écrire un petit menuet dans le style de Mozart’. I saw at once that it was time to act promptly, so I said in my best French: ‘Look here, I have given up my time, my work, my friends, and my career to come here and learn from you, and I am not going to write a petit menuet dans le style de Mozart.’ After that we became great friends and I learnt much from him. For example, that the heavy contrapuntal Teutonic manner was not necessary … He showed me how to orchestrate in points of colour rather than in lines … He was horrified that I had no pianoforte at the little hotel … «Sans le piano on ne peut pas inventer des nouvelles harmonies».

The Ravel experience led to a string quartet which caused a friend to remark with approximate percipience that RVW ‘must have been having tea with Debussy’—and yet Ravel referred approvingly to his erstwhile pupil as the only one of his who ‘n’écrit pas de ma musique’ (‘doesn’t write my music for me’). The effects on RVW’s development were generally oblique and subtle, refining and extending technique rather than deflecting the underlying idiom. As such, they encourage an interesting comparison between the early cycle The house of Life (1904) and the other works on this recording, three of them dating from the years immediately following Ravel’s interventions, and one from some three decades later.

In 1903 RVW wrote to the critic Edwin Evans, who was preparing an article about him. The letter listed principal works to date, including a Symphonic Rhapsody ‘after a poem by Christina Rossetti’ and also a slightly earlier setting, for soprano, chorus and orchestra, of Swinburne’s The Garden of Proserpine. The Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic hovers over these poetic choices, and it is unsurprising that in the year following the Evans letter RVW composed a cycle setting poems by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, brother of Christina and, in addition to his poetic activity, a leading light of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as a painter. The cycle was The house of Life and it incorporated ‘Silent noon’, a single song composed the previous year. Here we encounter some of the legacy of RVW’s study with Max Bruch in Berlin during 1897-98, and also of his earlier apprenticeship under Charles Villiers Stanford—who in RVW’s words had found him ‘too Teuton already’ and whose advice to go to Italy had been rejected. Both Stanford and Bruch deplored RVW’s harmonic predilection for flattened sevenths (something that would come fully into its own when he began collecting and arranging English folk songs). ‘Love-sight’, the song which opens The house of Life, betrays a degree of uncertain tension between instinct and schooling; likewise a tendency towards uniformity in the matching of bar length to the actual rate of harmonic change. Vocal lines are often doubled a little needlessly by the piano, denying the kind of textural transparency encouraged later by Ravel’s far-reaching guidance on orchestration. The way in which the more agitated central stages of the song (‘O love—my love! if I no more should see / Thyself …’) describe first a downward and then an upward chromatic sequence feels a shade obvious in its contrivance, and one senses a little of what was soon to lead the composer to Ravel’s door. In particular, one may be aware of the self-sufficiency of the piano-writing, from which the vocal line threatens to arise as a by-product rather as than the true compositional focus. Yet, there are tantalizing glimpses of things yet to come, still a few years off.

‘Silent noon’ offers relatively little contrast with the opening song except in tonality, but deploys a greater independence and melodic authenticity of vocal line. ‘Love’s minstrels’ alternates yet more of the textures from the previous two songs with free recitative-like passages, its piano-writing strongly suggesting a draft sketch for an orchestral arrangement. It hints immediately at the dense chordal opening texture of the Five Mystical Songs of 1911, but also at the ‘false-relation’ technique (juxtaposing ordinary triad chords such that one, two or three notes within them fruitfully ‘disagree’ with the content of the chord following) which was to emerge more fully in the string masterpiece Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis (1910, revised in 1913 and 1919). The sense of an orchestra waiting in the wings recurs in the chordal formations of the remaining numbers: notably the fanfare figures of ‘Death in Love’ and the more serene harmonic agglomerations of ‘Love’s last gift’, whose opening fleetingly prefigures the composer’s oft-heard short motet O taste and see (1952, sung at RVW’s funeral in 1958) or his Sine nomine tune for the hymn ‘For all the saints’.

RVW was by no means alone in turning to France for inspiration and enlightenment. The early music of Frank Bridge reveals an indebtedness to the craft, manner and harmonic flexibility of Fauré’s early chamber works, while E J Moeran’s first orchestral rhapsody contains a central allegro powerfully influenced by Ravel; similarly, salient moments of John Ireland’s cello sonata proclaim Debussy, and the current revival of interest in York Bowen has revealed his keen contemporaneous awareness of Debussy’s keyboard-writing. Although this indicates how the supposed cul de sac of nineteenth-century Germanic academicism is only a part of the story of British music in the early years of the century following, it does also highlight the danger of merely exchanging one form of import for another. Meanwhile, in a world destined to change utterly in the face of the First World War, folk-song collectors such as Cecil Sharp were rescuing an indigenous British heritage at risk of vanishing for ever. In his essay ‘The evolution of the folk-song’, RVW later wrote that:

The folk-song is I believe not dead, but the art of the folk-singer is. We cannot, and would not if we could, sing folk-songs in the same way and in the same circumstances in which they used to be sung. If the revival of folk-song meant merely an attempt to galvanize into life a dead past, there would be little to be said for it. The folk-song has now taken its place side by side with the classical songs of Schubert … Is not folk-song the bond of union where all our musical tastes can meet? … And where can we look for a surer proof that our art is living than in that music which has for generations voiced the spiritual longings of our race?

Herein lay the seeds of what blanket terminology has dubbed ‘The English Renaissance’: the birth of a nationalist vein of composition in which the modal harmony implicit in the contours of English folk song mapped naturally onto what was similarly implied by ancient plainchant, the origin of medieval choral polyphony. The confluence of these elements is central to the development of RVW’s language beyond The house of Life, and also to what we might call the spiritual dimension of his subsequent output as a whole. It meant that the living pulse of an indigenous recent and distant past beat just as strongly in works which by their nature might seem to borrow genuine folk melody but which were actually free extensions that simply ‘spoke its language’. RVW’s folk-song arrangements were therefore no mere appendix to his ‘real’ output, but intrinsic components of it.

The 15 Folk songs from the Eastern Counties were collected by RVW himself and published in his arrangements in 1908. Originating from Norfolk, The saucy bold robber exhibits a new confidence in textural economy, varying the pianistic textures for the paired verses. The exhortations of Stanford and Bruch to avoid modally flattened sevenths have no place here and are happily forgotten. The central outbreak of fisticuffs calls forth a spare running pattern of chromatic quavers in the accompaniment, with the contours of the tune left to imply their own harmony while the piano confines itself to rhythmic impetus. The Cambridgeshire song Harry the tailor contents itself with less textural variety but retains the same deft spareness. It spices its prevailing modality with occasional touches of false-relation harmony, including the concluding pair of chords.

Parts of the cycle On Wenlock Edge (1909) existed before finding their place within its overall scheme. Michael Kennedy notes that the sketches for ‘Clun’ date from 1906, the year before RVW’s lessons with Ravel, while ‘Is my team ploughing?’ was first performed ten months before the complete cycle, as a song for voice and piano only. Nonetheless, the work contains a variety of moments and effects plausibly attributable to Ravel’s influence—or, if not to that, then to the prior instincts which RVW had told Calvocoressi he was already feeling but needed to hear independently confirmed.

The vocal style of On Wenlock Edge is predominantly syllabic (one syllable per note), with only very occasional melismas (groupings of successive notes within a single vowel sound) deployed to highlight effects such as the fitful gusts of wind in the swirling first movement. The second movement’s opening clearly emanates from the same general inspiration as that of the Tallis Fantasia. The emotional core of the cycle lies in its third and fifth movements, which are separated by only the most fleeting of burlesques: a well-judged respite between two passages of sustained intensity.

‘Is my team ploughing?’ displays a new psychological insight, delineating the drama played out between the living and the departed by alternating muted strings for the voice from below ground with repeated piano chords for the no less unquiet spirit above it. In other contexts the resulting climax could have conveyed spiritual or sensual exultation; but this is short-lived and soon replaced by final disconsolate murmurings from the grave. ‘Bredon Hill’ retains the muted strings, initially balancing them with subdued piano chords to embody what the poet Matthew Arnold captured as ‘All the live murmur of a summer’s day’—a line later set by RVW in An Oxford Elegy (1949). From the stillness progressively emerge distant steeple bells, which rise to a contented tumult before receding again. What follows is a master stroke of simple transformation, as the song’s opening chord is recognizably reprised in altered harmonic form. The expressionist exterior landscape becomes a midwinter of the spirit and a world numbed by loss. Listening to the tolling of the funeral bell (conjured by both plucked and bowed violins doubling the piano), it is easy to imagine the further influence of Ravel, who greatly admired this work by his pupil; but one thinks also of that more macabre bell that permeates ‘Le gibet’, the central tone poem in Ravel’s piano triptych Gaspard de la nuit. Ravel was working on this during 1908, almost immediately after his sessions with RVW—but, as previously noted, parts of On Wenlock Edge already existed in 1906. If there was a line of influence, in which direction did it run? Recurring as if to lend point to this question, Shropshire’s church bells now turn oppressive, their tumult mocking the condition of the speaker’s bereft spirit. After the brokenness of the final, resigned ‘I will come’, the focus recedes and the observation becomes more distant in ‘Clun’, where the fleeting smallness of human life is reflected by a widening vista: the peace of rural Shropshire; the distant bustle of London; an unnamed world beyond this one. The ‘doomsday’ that ‘may thunder and lighten’ at the last seems to be a conflation of the individual’s day of reckoning with ‘Domesday’, that feudal record of Norman England which ‘spared no man, but judged all men indifferently’ (William Lambarde, A perambulation of Kent, 1570).

RVW pragmatically envisaged performances of On Wenlock Edge with only a piano available, and the score contains many alternative deployments for the pianist to adopt in the absence of strings. The work was first performed, with full complement, in London on 15 November 1909. It was published in 1911. A third version, for orchestra, was performed in London on 24 January 1924, under the composer’s baton. Such flexibility is evident also in the Four Hymns (1914), conceived for tenor voice with viola solo and piano; or viola solo and string orchestra; or piano with string quartet (the same forces as Wenlock). Their first performance, delayed by war, occurred in Cardiff on 26 May 1920, in the second of their instrumental guises, conducted by Julius Harrison. The London premiere followed on 19 October that year, with RVW himself conducting similar forces.

The Four Hymns set two poets of the earlier seventeenth century, one from the turn of the eighteenth and one free translation from third-century Greek by Robert Bridges which had appeared in his Yattendon Hymnal (1894-99) and had been incorporated into The English Hymnal under the musical editorship of RVW in 1906. Melismatic vocal writing is more freely deployed here for purposes of heightened expression, and the vocal line often rises to operatic heights of pitch. Piano parts are largely self-sufficient, unsurprisingly given the provisional approach taken to available instrumentation. The declamatory first hymn moves freely in both its seamlessly fluctuating time signatures and its easy unifying of folk song and ancient church modality. The second presents an austere contrast, enhanced by the mixed Phrygian and Dorian modality of its initial theme. The hushed third hymn’s voiceless opening prefigures the chains of simple triads that begin the composer’s ‘Pastoral’ third symphony (1922). The last features a ground bass, its recurrent idea at odds with the bar length, thus imparting simultaneous unity and diversity to the texture. This finale approach was to be repeated in the passacaglia movement ending RVW’s beatific fifth symphony (1943, revised in 1951). The fourth hymn swells into a triumphant processional before subsiding to a serenely hushed conclusion.

The Six English folk songs were arranged in 1935. A Dorset cousin of Harry the tailor, The brewer ‘without any barm’ (yeast) makes for a rather fleeting experience. Happily, Mr Spence here shows himself more than a little fecund in the positing of comparable predicaments …

Francis Pott © 2022